So, you know how in part 1 I said that FiveThirtyEight

estimated that there would be 1,000 deaths at the hands of police each year? I

spent months researching this question using data from Killedbypolice.net (KBP) to

conclude … there were exactly 1,000 deaths due to a police officer’s lethal act

of force.

Not “around” 1,000. Exactly

1,000.

I didn’t set out to find 1,000. I didn’t interpret the data

more favorably in order to stretch the number to 1,000. It just happened that

way.

Of those 1,000 people killed by lethal acts of force, 938

were killed by gunfire, 39 were killed after being tased, and 23 died from

other causes like physical restraint or battery, like being placed in a

chokehold and taken to the ground (like Eric Garner).

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) found that from 2003 to

2005, 96% of homicides by police were caused by gunshots, though that figure

only includes known police homicides, making up 55% of all arrest-related

deaths, and does not include the 8% of arrest related deaths that were due to

unknown causes.[1]

Since the KBP data tends to include these unknown cause deaths as police

homicides, it makes sense that the percentage of gunshot deaths in my database

would be lower than the percentage in the BJS report.

95% of those who were killed by lethal acts of force in 2014

were males, and 5% were females.

This figure is similar to figures found from other

sources. The Bureau of Justice

Statistics report for the years 2003 through 2005 found 97% of decedents are

men, as did the FBI’s Supplemental Homicide Report for the same years.[2]

The BJS report for 2003-2009 found this number to be 95.4% men and 4.5% women.[3]

Tasers

In 126 incidents (13%), there is documented evidence of an

officer using a taser beforehand to try to attempt an arrest without having to

resort to gunfire. I tried to count each instance where a taser was fired by a

police officer, whether or not it connected with the decedent or was effective

at all. This number includes the 39

incidents where the cause of death was likely the taser, and four where the

taser was used, but the decedent died by some other means. Two of the 39 people (5%) who died after

being tased were women (Iretha Lilly of Waco, Texas, and Jennifer Bond, who

died while traveling in Kentucky).

Veronica Canter of Fresno was the only example of a female who died from

police gunfire after having been tased.

This number of 126 uses of tasers is likely an undercount.

On a few occasions I found that the media did not report that an officer used a

taser to try and subdue the decedent before he or she was shot, but the taser

use was later revealed when the district attorney released a report about the

investigation. But in most of these

incidents, a report was never released publicly by the district attorney,

leaving the media’s post-incident report as the narrative-of-record.

There isn’t much data out there to compare this figure of

13% to. The 2003-2005 BJS Arrest-Related

Deaths report found 36 incidents where a taser was involved, and in 17 of those

cases the taser was the cause of death.[4] The report did not list a percentage of

arrest-related deaths that a taser was used in.

The San Diego County District Attorney’s office released a study

analyzing all officer-involved shootings between 1993 and 2012. In this report,

the attorney’s office found that tasers were used in 9 of the 358 shooting

events, which is 2.5% of all shootings.[5]

I found tasers were used in 83 of the 938 shootings nationwide, which is a rate

of 9.1%. Considering how tasers weren’t

even used by police before 1998, it is not surprising that my count would be

higher than the San Diego count that includes data from as far back as 1993.[6]

There is some controversy over the citation of tasers as a

cause of death. Before 2014, a taser (or rather, a conducted electronic device

similar to the one manufactured by TASER International, which I’m going to

continue to call a “taser” with a lower-case t, sorry red squiggly line) had never

been cited in an official cause of death report in Florida.[7]

Most of the people in Florida who had been killed by the police and had been

tased got documented as having died from “excited delirium”, which is brain

malfunction, quite rare, that makes people highly aggressive and full of

feverish rage. It’s so rare in fact that almost all reported cases of someone

having “excited delirium” involve people involved in a physical struggle with

police.[8]

I found that people who died due to a police officer’s taser

were more likely to have been black than any other race. Though black people only account for about 12.5%

of the population of the United States, they accounted for 46% of the deaths

due to tasing in 2014. This was similar

to the percentage of deaths of black people due to tasers found by the BJS

report on arrest-related deaths from 2003 to 2005. In that report, the BJS

found that 48.5% of taser-related deaths happened to black people, while 45.5%

happened to white people and 6.1% (2 incidents) happened to Hispanic or Latino people.

Physical struggles

A physical struggle

took place in 163 incidents of lethal acts of force in 2014 (16%). This counts basically any touch of the police

officer on the decedent where the officer attempted to restrain, kick, punch,

hold down or grab the decedent, no matter who started the fight. Batons count as a physical struggle for these

purposes.

Of those 163 incidents, 114 people died from police

officers’ gunshots later, while 27 people died after being tased. 22 people who

were entangled in a physical struggle with police died from non-gunshot,

non-taser related injuries likely caused by police. Not counted as a physical struggle but

counted as a non-gunshot non-taser death was the May 24 death on Skid Row of Carlos Ocana

by the Los Angeles Police Department. Ocana had

climbed up a billboard on top of a roof. He had come down from the billboard on

his own, but then he became spooked by the SWAT team’s guns and started to clamber

back up. LAPD officers tased him, and Ocana lost his grip. Ocana plummeted to

the asphalt below, where an inflatable pad had been placed, but in the wrong

location.[9]

The death was an accidental death, but the use of force in that incident was

not accidental.

Race

I tried to attribute a race to each decedent found in the

KBP database. KBP had already found the race of the decedent in 38% of the

cases (376) at the time I scraped the data, which was late December of 2014.

The task of finding the race in the remaining 624 incidents often took up a lot

of time. Most law enforcement agencies

don’t release the race of the person they killed, and most pieces from media

sources don’t include the information in any narrative, though frequently a

driver’s license picture or recent booking photo of the decedent will be

included in the article, and occasionally these will have been missed by the

KBP data.

I had to use my best internet searching skills (partially

learned from one of my other hobbies, genealogy) to find the answer to the

question of race. Sadly one great source of information was Mugshots.com, especially for decedents who had a criminal history and an unusually unique name. Obituaries and funeral

notices were also a particularly good source of information on race. Funeral homes frequently post a picture of the

decedent and an age and date of death, which can be used to confirm the

identity of the decedent. However there were many obituaries where no picture was included. For

those I had to try to find the race of the family members mentioned in the

obituary, in particular siblings and children rather than spouses, which can give the possibility of a false positive due to interracial coupling. Yes, I used publicly available social network

profiles on a few occasions to track down family members in order to determine

the race of the decedent. In about 40

incidents I used an assumption about the likely race of the decedent, but only

where a strong ~80% sure assumption could be made based on the neighborhood

where the decedent lived, the name of the person, and the circumstances of the incident. Still, I was unable to

confirm the race of the decedent in 31 of the lethal act of force incidents in

2014.

I used the classification scheme that the BJS uses in their

Arrest-Related Deaths report. “White” for this project means non-Hispanic white.

“Black” similarly means non-Hispanic black.

Unlike the BJS, I placed people with more than one race or

ethnicity into one race or another based on a chronological sequence. That is,

I went down the list in chronological order, placing the first person in the

“white” category and the second in the “Hispanic or Latino” category, for

instance. I did this for mathematical reasons. At first I just classified

people as more than one race, but I realized that this would lead to a higher

rate of death for a given race than is reflected in reality. I also didn’t want

to classify bi-racial people as a different race called “other” because then

the statistics for each of these incidents would be lost to the bucket of

“other”ness where one can’t use data to see trends because the data isn’t

reflective of any single race. There

were 19 people I identified as being bi-racial (or bi-ethnic): 3 were white and

black, 14 were Hispanic and non-Hispanic white, one was Asian and white, and

one was Hispanic and Native American.

Through my partitioning method, these incidents became categorized as

occurring to 2 black people, 7 Hispanic or Latino people, 1 native American and

9 white people.

For all deaths caused by a police officer’s lethal act of

force, 266 were black, 486 were white, 185 were Hispanic or Latino, 14 were

Asian, 13 were Native American, and 36 were unknown or another race. Excluding those whose race was unknown, the

percentages change very little.

The BJS found that the racial breakdown for police homicides

from 2003 to 2005 was 44.8% white, 29.9% black, 20.2% Hispanic or Latino, and

5.1% for all others.[10]

Their report for 2003 to 2009 showed 41.7% white, 31.7% black, 20.3% Hispanic

or Latino, and 6.4% for all others.[11]

My analysis for 2014 shows more white people and fewer people of color than the

BJS reports. My theory is that the gaps in the numbers for BJS data come from

sheriff’s offices and small town police departments, which are demographically

more likely to be responsible for the deaths of white people.

Age

I found that the average age of people who died due to an

officer’s lethal act of force in 2014 was 35.9 years, while the median decedent

was 34 years old.

Median age

|

Average age

|

Most frequently occurring age

|

|

All lethal acts of force

|

34

|

35.9

|

27

|

Gun deaths only

|

34

|

35.8

|

29

|

Taser deaths only

|

37

|

35.8

|

30

|

The BJS report on data from 2003 to 2005 and the FBI’s supplemental

homicide report for the same time frame found the average age was 33 years old.[12]

The age group with the most deaths in 2014 was the 24 to 29

year old range, with 194 people killed.

Death rate

I found that the rate of death for the entire country in

2014 was 3.14 people per million. But the rate varied by race and age.

Jaeah Lee, in a piece for Mother Jones, looked into the BJS

report from 2003 to 2009 and found that black people were killed at an average

annual rate of 3.66 deaths per million, while white people were killed at an

average annual rate of 0.90 deaths per million.[13] The rates I found are higher than Lee’s.

Death rate per million per year

|

As found by Jaeah Lee using BLS data from 2003-2009

|

My analysis

|

% difference

|

Black

|

3.66

|

6.67

|

182%

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

1.92

|

3.41

|

178%

|

White

|

0.90

|

2.36

|

262%

|

While it seems that the BLS data undercounts all races, it

undercounts white decedents more than black and Hispanic or Latino decedents.

This is not to say that white people are more likely to die than black people,

just that black people may only be three times as likely to die from a police

officer’s lethal act of force than a white person, rather than four times as

likely, as Lee stated in her article.

The rate is much higher for men than for women, and much

higher for black men than for white and Hispanic men.

Males, death rate per million per year

|

Females, death rate per million per year

|

|

All (n=1000)

|

5.9 (n=947)

|

0.3 (n=53)

|

White (n=483)

|

4.4 (n=451)

|

0.3 (n=32)

|

Hispanic (n=184)

|

6.4 (n=177)

|

0.3 (n=7)

|

Black (n=264)

|

13.0 (n=255)

|

0.4 (n=9)

|

And the rate is higher for young men than for older men, and

higher for young black men than for young white and young Hispanic men.

Death rate per million per year

|

10 to 17 year old males

|

18 to 34 year old males

|

35 to 64 year old males

|

65 year old males and older

|

All

|

0.9 (n=16)

|

12.0 (n=462)

|

6.7 (n=424)

|

1.7 (n=32)

|

White

|

0.3 (n=3)

|

8.1 (n=180)

|

5.7 (n=245)

|

1.5 (n=23)

|

Hispanic

|

1.3 (n=5)

|

12.1 (n=99)

|

8.1 (n=71)

|

1.5 (n=2)

|

Black

|

2.7 (n=7)

|

30.6 (n=159)

|

11.5 (n=83)

|

4.0 (n=6)

|

While young (18 to 34 year old) black men account for only

2% of the population of the United States, they accounted for 16% of decedents

killed by lethal acts of police force in 2014.

ProPublica ran an analysis in October of 2014 that compared

the rate at which white teenagers get killed to the rate that black teenagers

get killed. Using FBI data they found

that white males between 15 and 19 years old got killed by police at a rate of

1.47 per million over the three year time period between 2010 and 2012, while

black males between 15 and 19 years old got killed by police at a rate of 31.17

per million.[14] Given that this rate was over a three year

time period, I’ll make an assumption that the annual rate can be found by

dividing by three in order to compare it to my analysis. ProPublica’s rate per million was therefore

0.49 per year for white males between 15 and 19 years old, while the rate per

million for black males of the same age range was 10.39 per year.

I found a similar death rate per million for black teenage

males, but the rate of white teenage males I found was approximately three

times higher than what ProPublica found.

Death rate per million per year, males only, 2014

|

Number of deaths, ages 15 to 19

|

Rate per million per year, ages 15 to 19

|

All

|

45

|

3.9

|

White

|

12

|

1.8

|

Hispanic

|

12

|

4.9

|

Black

|

18

|

10.2

|

The authors of the ProPublica study did not emphasize the

absolute rate per million but rather the difference in likelihood of death

between black teenagers and white teenagers. They said that black teenagers

were 21 times more likely to be killed by police than a white teenager. After

some experts criticized their analysis in part for using such flawed data,

ProPublica looked at other three-year chunks of FBI data to see if there were

similar black-to-white risk ratios in prior years. They found that the rate had

been as low as 9 times more likely and as high as 21 times more likely going

back to 2006.[15]

I found that black teenagers were 5.5 times more likely to

be killed by police in 2014 than white teenagers of the same age. I attribute

this lower rate to the fact that the police forces most likely to report data

to the FBI are also the police forces most likely to have committed a lethal

act of force against a black person; that is, larger forces from big cities.

The biggest racial disparity I found in terms of relative

likelihood of dying due to police lethal acts of force was over the age range

of 20 to 24. For 2014, I found that black males in that age range (at a rate of

34.0 deaths per million per year) were 6.9 times more likely to die from a

police officer’s lethal act of force than a white male between 20 and 24 (4.9

deaths per million per year).

Deaths in 2014 in the US by police lethal acts of force, males only, by age group

|

All

|

White

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

Black

|

0 to 4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

5 to 9

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

10 to 14

|

3

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

15 to 17

|

13

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

18 to 19

|

32

|

9

|

8

|

13

|

20 to 24

|

133

|

33

|

35

|

58

|

25 to 29

|

166

|

75

|

33

|

51

|

30 to 34

|

131

|

63

|

23

|

37

|

35 to 44

|

218

|

112

|

43

|

53

|

45 to 54

|

154

|

96

|

21

|

25

|

55 to 64

|

52

|

37

|

7

|

5

|

65 to 74

|

26

|

17

|

2

|

6

|

75 to 84

|

5

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

85 and over

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

Deaths per million per year, males only, by age group, in 2014 in the US

|

All

|

White

|

Hispanic

|

Black

|

0 to 4

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

5 to 9

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

10 to 14

|

0.3

|

0.0

|

0.4

|

1.3

|

15 to 17

|

1.9

|

0.8

|

2.8

|

4.9

|

18 to 19

|

6.6

|

3.4

|

7.9

|

17.5

|

20 to 24

|

11.2

|

4.9

|

14.1

|

34.0

|

25 to 29

|

14.8

|

11.6

|

13.8

|

35.9

|

30 to 34

|

12.2

|

10.1

|

10.0

|

27.9

|

35 to 44

|

10.2

|

8.6

|

10.7

|

20.5

|

45 to 54

|

6.7

|

6.1

|

7.0

|

9.3

|

55 to 64

|

2.7

|

2.6

|

4.0

|

2.6

|

65 to 74

|

2.3

|

1.9

|

2.4

|

6.3

|

75 to 84

|

0.9

|

1.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

85 and over

|

0.5

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

A note on population figures

I tried to use US Census data for population numbers broken

down by race, but these have not yet been published for 2014. Instead I used

the race and age breakdown from the 2009-2013 American Community Survey (ACS) and

“scaled up” to the total number of people from the 2014 US census data. This

method is simple but it assumes that the proportion of each race and age

category remains constant year over year, which would not be true. I also chose

to distribute people who were “more than one race” and “some other race”

proportionally to each race and age group in the same way.

2009-2013 ACS census population

|

2014 Census estimate for purposes of finding rates of death

|

|

Non-Hispanic white alone

|

197,050,418

|

206,312,263

|

Hispanic (any)

|

51,786,581

|

54,220,675

|

Non-Hispanic black alone

|

38,093,998

|

39,884,508

|

Non-Hispanic Asian alone

|

15,061,411

|

15,769,334

|

Non-Hispanic American Indian alone

|

2,061,752

|

2,158,659

|

Non-Hispanic Pacific Islander

alone

|

488,646

|

511,614

|

Sum

|

304,542,806

|

318,857,053

|

Census total

|

311,536,594

(including people of more than one race and people of “some other race”) |

318,857,052

(from US Census estimates for 2014) |

Armed

Overall, 18% of people killed by a police officer’s lethal

act of force in 2014 were unarmed.

This figure includes deaths caused not only by gunshot, but

also by taser or through some other means.

The vast majority of deaths caused by a taser discharge were

against unarmed people.

This is expected, and I think it’s important confer a lesser

degree of culpability on the officer involved in a death by taser, since the

officer never intended to use lethal force. But when an officer uses a real

firearm, like Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, he or she generally intends on

killing the person. And yet still, 13% of those who died from officer gunfire

in 2014 were unarmed. That’s 119 people.

There was a difference depending on the decedent’s

race. 62% of the white people who died

due to a lethal act of force had guns, and 14% were unarmed. Only 51% of black

people who died due to a lethal act of force had guns, and 25% were unarmed.

For Hispanic people, only 48% of those killed by police had guns, and 20% were

unarmed.

Since taser deaths had a tendency in 2014 to occur to black

people more than to white people or Hispanic or Latino people, and since those

who died by tasers were overwhelmingly unarmed, one would expect the number of

unarmed people who died by lethal acts of force to be at an increased level for

black people than for white people and Hispanic people due to this taser

effect. But the racial disparity in

unarmed killings is still present even when gunshot deaths are isolated.

While only 10% of gunshot deaths of white people were to

those not carrying arms, 17% of the gunshot deaths of black people happened to

unarmed people. And unarmed Hispanic

people were killed at almost the same rate, 16%, while barely half of the

Hispanic deaths involved people with guns, the lowest of these three

race/ethnicity categories.

It is difficult to strike a comparison with any published

data to these numbers. The BJS report for the data collected between 2003 to

2005 found that in 80.1% of the arrest-related homicides committed by police

the arrestee had used a weapon to threaten or assault officers.[16] For my analysis, this number would be

somewhat comparable to the 82% of people who were armed, although I include in

that total people who weren’t threatening officers but were only threatening or

assaulting other victims when they were shot by police (5% of the incidents).

Viewing the data another way, I analyzed the race of the

weapon-carrying decedents. Of all the gun-toting people who were killed by a

lethal act of force in 2014, 54% were white and only 25% of them were black.

But of all the unarmed people killed by a lethal act of force in 2014, just 38%

were white and 37% were black.

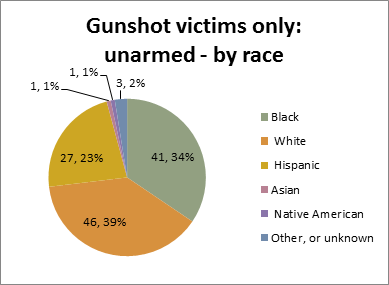

Focusing in only on gunshot victims, the percentage of unarmed

people who were black shrinks, but only to 34% compared to 39% of unarmed

people who were white.

These are the crosstabs.

All acts of force, 2014

|

Total

|

Black

|

White

|

Hispanic

|

Asian

|

Native American

|

Other, or unknown

|

Had a gun

|

553

|

136

|

301

|

89

|

3

|

7

|

17

|

Had a knife

|

182

|

39

|

85

|

36

|

9

|

5

|

8

|

Had a car

|

61

|

19

|

25

|

11

|

1

|

0

|

5

|

Had another weapon

|

28

|

6

|

8

|

12

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

Unarmed

|

176

|

66

|

67

|

37

|

1

|

1

|

4

|

All acts of force, 2014

|

Total

|

Black

|

White

|

Hispanic

|

Asian

|

Native American

|

Other, or unknown

|

Had a gun

|

100.0%

|

24.6%

|

54.4%

|

16.1%

|

0.5%

|

1.3%

|

3.1%

|

Had a knife

|

100.0%

|

21.4%

|

46.7%

|

19.8%

|

4.9%

|

2.7%

|

4.4%

|

Had a car

|

100.0%

|

31.1%

|

41.0%

|

18.0%

|

1.6%

|

0.0%

|

8.2%

|

Had another weapon

|

100.0%

|

21.4%

|

28.6%

|

42.9%

|

0.0%

|

0.0%

|

7.1%

|

Unarmed

|

100.0%

|

37.5%

|

38.1%

|

21.0%

|

0.6%

|

0.6%

|

2.3%

|

Died by gunshot only, 2014

|

Total

|

Black

|

White

|

Hispanic

|

Asian

|

Native American

|

Other, or unknown

|

Had a gun

|

553

|

136

|

301

|

89

|

3

|

7

|

17

|

Had a knife

|

181

|

39

|

84

|

36

|

9

|

5

|

8

|

Had a car

|

60

|

19

|

24

|

11

|

1

|

0

|

5

|

Had another weapon

|

25

|

5

|

7

|

11

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

Unarmed

|

119

|

41

|

46

|

27

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

Died by gunshot only, 2014

|

Total

|

Black

|

White

|

Hispanic

|

Asian

|

Native American

|

Other, or unknown

|

Had a gun

|

100.0%

|

24.6%

|

54.4%

|

16.1%

|

0.5%

|

1.3%

|

3.1%

|

Had a knife

|

100.0%

|

21.5%

|

46.4%

|

19.9%

|

5.0%

|

2.8%

|

4.4%

|

Had a car

|

100.0%

|

31.7%

|

40.0%

|

18.3%

|

1.7%

|

0.0%

|

8.3%

|

Had another weapon

|

100.0%

|

20.0%

|

28.0%

|

44.0%

|

0.0%

|

0.0%

|

8.0%

|

Unarmed

|

100.0%

|

34.5%

|

38.7%

|

22.7%

|

0.8%

|

0.8%

|

2.5%

|

A note on privacy

I have found the vast majority of the victim names through

information published by local media and aggregated by Killedbypolice.net, with

the exception of a handful of names in the Houston region that were never

released publicly. These Houston names

do appear in the Texas Attorney Generals Custodial Deaths Report, mandated by

state law to be released to the public.[17] All the officer names I have found published

in local media after the information was allowed to be released by the local

police departments, or sometimes through the investigative reports released to

the public by district attorneys and prosecutors.

In most instances, the victim’s name is only released to the

public after the victim’s family has been informed of the victim’s death. In

many cases, the officer’s name gets released to the public only after the

officer consents to it being released, but it varies by jurisdiction. The name

of the officer or officers involved has been released in only 53% of the

incidents in my database. A California

Supreme Court ruling in 2014 found that the public has a right to know the

names of police officers involved in on-duty shootings unless specific safety

concerns against officers, not vague assertions of possible threats, could be

articulated.[18]

I agree with the opinion of the California Supreme Court,

that a public has a right to know the identity of the police officer involved,

a public figure who wears his name on his uniform as he goes about doing

service for the public. And I feel that

not disclosing the names of the victims does a disservice to the public in

terms of the ability to investigate and research police use of force.

Throughout this essay, I use both the names of the victims and the names of the

officers involved in the shooting.

[1]

Mumola, Christopher J. “Arrest-Related Deaths in the United States, 2003-2005”.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, October 11, 2007. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=379

[2]

Mumola, Christopher J. “Arrest-Related Deaths in the United States, 2003-2005”.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, October 11, 2007. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=379

[3]

Burch, Andrea M. “Arrest-Related Deaths, 2003-2009 – Statistical Tables”.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, November 17, 2011. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=2228

[4]

Mumola, Christopher J. “Arrest-Related Deaths in the United States, 2003-2005”.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, October 11, 2007. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=379

[5]

“Officer-Involved Shooting Review: Analysis of Cases Reviewed by the San Diego

County District Attorney’s Office 1993-2012”. San Diego County District

Attorney’s Office, December 2014. http://www.sdcda.org/files/OIS_20YrReport_Final.pdf

[6]

Markos, Kibret. “Stun Guns Catch On Slowly With N.J. Cops”. The Record,

December 13, 2014. http://www.northjersey.com/news/stun-guns-catch-on-slowly-with-n-j-cops-1.1152867?page=all

[7]

Ovalle, David, and Charles Rabin. “Teen Shot By Miami Beach Police Taser Died

of Accidental Cardiac Arrest”. Miami Herald, March 6, 2014. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article1961084.html

[8]

Sullivan, Laura. “Death By Excited Delirium: Diagnosis or Coverup?” NPR,

February 26, 2007. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=7608386

[9]

Holland, Gale. “Skid Row Residents Criticize LAPD After Death of Mentally Ill

Man”. Los Angeles Times, July 2, 2014. http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-skid-row-death-20140702-story.html

[10]

Mumola

[11]

Burch

[12]

Mumola

[13]

Lee, Jaeah. “Here’s the Data That Shows Cops Kill Black People at a Higher Rate

Than White People”. Mother Jones, September 10, 2014. http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/08/police-shootings-ferguson-race-data

[14]

Gabrielson, Ryan, Ryann Grochowski Jones, and Eric Sagara. “Deadly Force, in

Black and White”. ProPublica, October 10, 2014. http://www.propublica.org/article/deadly-force-in-black-and-white

[15]

Gabrielson, Ryan, and Ryann Grochowski Jones. “Answering the Critics of Our

Deadly Force Story”. ProPublica, December 24, 2014. http://www.propublica.org/article/answering-the-critics-of-our-deadly-force-story

[16]

Mumola

[17]

“Custodial Death Reports”. Attorney General of Texas Ken Paxton’s public

website. https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/criminal/custodial/report_deaths.php

[18]

Puente, Kelly. “Court: Names of Officers in Shootings Should Usually Be

Public”. Orange County Register, May 29, 2014. http://www.ocregister.com/articles/officers-616324-officer-court.html

No comments:

Post a Comment